%matplotlib inline

# data wrangling / viz

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sn

# stats / machine learning

from imblearn.over_sampling import SMOTE

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

from imblearn.pipeline import Pipeline

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

from sklearn.metrics import average_precision_score

from sklearn.metrics import precision_recall_curve

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV

from sklearn.ensemble import VotingClassifier

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

from sklearn.metrics.cluster import homogeneity_score

from sklearn.metrics.cluster import silhouette_score

# text mining

#!pip install nltk

import nltk

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

import string

import gensim

from gensim import corpora

#!pip install pyLDAvis

import pyFraud Detection in Python

1. Introduction and preparing your data

In this section, we’ll learn about the typical challenges associated with fraud detection, and will learn how to resample our data in a smart way, to tackle problems with imbalanced data.

1.1 Dataset

The original dataset contains transactions made by credit cards over two days in September 2013 by European cardholders. The dataset is highly unbalanced.

Machine Learning algorithms usually work best when the different classes contained in the dataset are more or less equally present. If there are few cases of fraud, then there’s little data to learn how to identify them. This is known as class imbalance, and it’s one of the main challenges of fraud detection.

Let’s explore this dataset, and observe this class imbalance problem.

Libraries & packages

1.1.1 Checking the fraud to non-fraud ratio

df = pd.read_csv('data/creditcard.csv')

df| Time | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | V9 | ... | V21 | V22 | V23 | V24 | V25 | V26 | V27 | V28 | Amount | Class | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0 | -1.359807 | -0.072781 | 2.536347 | 1.378155 | -0.338321 | 0.462388 | 0.239599 | 0.098698 | 0.363787 | ... | -0.018307 | 0.277838 | -0.110474 | 0.066928 | 0.128539 | -0.189115 | 0.133558 | -0.021053 | 149.62 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.0 | 1.191857 | 0.266151 | 0.166480 | 0.448154 | 0.060018 | -0.082361 | -0.078803 | 0.085102 | -0.255425 | ... | -0.225775 | -0.638672 | 0.101288 | -0.339846 | 0.167170 | 0.125895 | -0.008983 | 0.014724 | 2.69 | 0 |

| 2 | 1.0 | -1.358354 | -1.340163 | 1.773209 | 0.379780 | -0.503198 | 1.800499 | 0.791461 | 0.247676 | -1.514654 | ... | 0.247998 | 0.771679 | 0.909412 | -0.689281 | -0.327642 | -0.139097 | -0.055353 | -0.059752 | 378.66 | 0 |

| 3 | 1.0 | -0.966272 | -0.185226 | 1.792993 | -0.863291 | -0.010309 | 1.247203 | 0.237609 | 0.377436 | -1.387024 | ... | -0.108300 | 0.005274 | -0.190321 | -1.175575 | 0.647376 | -0.221929 | 0.062723 | 0.061458 | 123.50 | 0 |

| 4 | 2.0 | -1.158233 | 0.877737 | 1.548718 | 0.403034 | -0.407193 | 0.095921 | 0.592941 | -0.270533 | 0.817739 | ... | -0.009431 | 0.798278 | -0.137458 | 0.141267 | -0.206010 | 0.502292 | 0.219422 | 0.215153 | 69.99 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 284802 | 172786.0 | -11.881118 | 10.071785 | -9.834783 | -2.066656 | -5.364473 | -2.606837 | -4.918215 | 7.305334 | 1.914428 | ... | 0.213454 | 0.111864 | 1.014480 | -0.509348 | 1.436807 | 0.250034 | 0.943651 | 0.823731 | 0.77 | 0 |

| 284803 | 172787.0 | -0.732789 | -0.055080 | 2.035030 | -0.738589 | 0.868229 | 1.058415 | 0.024330 | 0.294869 | 0.584800 | ... | 0.214205 | 0.924384 | 0.012463 | -1.016226 | -0.606624 | -0.395255 | 0.068472 | -0.053527 | 24.79 | 0 |

| 284804 | 172788.0 | 1.919565 | -0.301254 | -3.249640 | -0.557828 | 2.630515 | 3.031260 | -0.296827 | 0.708417 | 0.432454 | ... | 0.232045 | 0.578229 | -0.037501 | 0.640134 | 0.265745 | -0.087371 | 0.004455 | -0.026561 | 67.88 | 0 |

| 284805 | 172788.0 | -0.240440 | 0.530483 | 0.702510 | 0.689799 | -0.377961 | 0.623708 | -0.686180 | 0.679145 | 0.392087 | ... | 0.265245 | 0.800049 | -0.163298 | 0.123205 | -0.569159 | 0.546668 | 0.108821 | 0.104533 | 10.00 | 0 |

| 284806 | 172792.0 | -0.533413 | -0.189733 | 0.703337 | -0.506271 | -0.012546 | -0.649617 | 1.577006 | -0.414650 | 0.486180 | ... | 0.261057 | 0.643078 | 0.376777 | 0.008797 | -0.473649 | -0.818267 | -0.002415 | 0.013649 | 217.00 | 0 |

284807 rows × 31 columns

# Explore the features available in your dataframe

print(df.info())<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 284807 entries, 0 to 284806

Data columns (total 31 columns):

# Column Non-Null Count Dtype

--- ------ -------------- -----

0 Time 284807 non-null float64

1 V1 284807 non-null float64

2 V2 284807 non-null float64

3 V3 284807 non-null float64

4 V4 284807 non-null float64

5 V5 284807 non-null float64

6 V6 284807 non-null float64

7 V7 284807 non-null float64

8 V8 284807 non-null float64

9 V9 284807 non-null float64

10 V10 284807 non-null float64

11 V11 284807 non-null float64

12 V12 284807 non-null float64

13 V13 284807 non-null float64

14 V14 284807 non-null float64

15 V15 284807 non-null float64

16 V16 284807 non-null float64

17 V17 284807 non-null float64

18 V18 284807 non-null float64

19 V19 284807 non-null float64

20 V20 284807 non-null float64

21 V21 284807 non-null float64

22 V22 284807 non-null float64

23 V23 284807 non-null float64

24 V24 284807 non-null float64

25 V25 284807 non-null float64

26 V26 284807 non-null float64

27 V27 284807 non-null float64

28 V28 284807 non-null float64

29 Amount 284807 non-null float64

30 Class 284807 non-null int64

dtypes: float64(30), int64(1)

memory usage: 67.4 MB

None# Count the occurrences of fraud and no fraud and print them

occ = df['Class'].value_counts()

print(occ)Class

0 284315

1 492

Name: count, dtype: int64# Print the ratio of fraud cases

print(occ / len(df))Class

0 0.998273

1 0.001727

Name: count, dtype: float64As we can see, the proportion of fraudulent transactions (denoted by 1) is very low. We will learn how to deal with this in the next section.

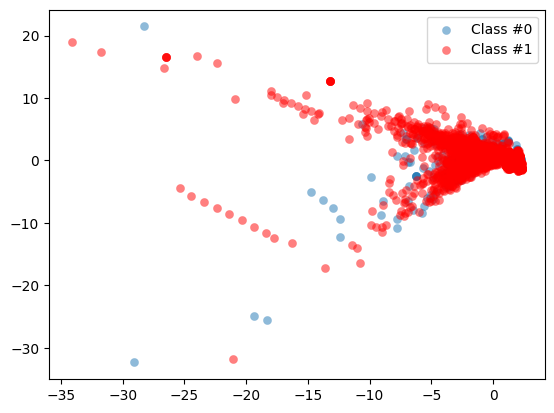

1.1.2 Plotting our data

Let’s look at the data and visualize the fraud to non-fraud ratio. It is always a good starting point in your fraud analysis, to look at your data first, before you make any changes to it. Moreover, when talking to your colleagues, a picture often makes it very clear that we’re dealing with heavily imbalanced data. Let’s create a plot to visualize the ratio fraud to non-fraud data points on the dataset.

def prep_data(df):

X = df.iloc[:, 1:29]

X = np.array(X).astype(np.float64)

y = df.iloc[:, 29]

y=np.array(y).astype(np.float64)

return X,y# Define a function to create a scatter plot of our data and labels

def plot_data(X, y):

plt.scatter(X[y == 0, 0], X[y == 0, 1], label="Class #0", alpha=0.5, linewidth=0.15)

plt.scatter(X[y == 1, 0], X[y == 1, 1], label="Class #1", alpha=0.5, linewidth=0.15, c='r')

plt.legend()

return plt.show()# Create X and y from the prep_data function

X_original, y_original = prep_data(df)# Plot our data by running our plot data function on X and y

plot_data(X_original, y_original)

By visualizing our data you can immediately see how scattered our fraud cases are, and how few cases we have. A picture often makes the imbalance problem very clear. In the next sections we’ll visually explore how to improve our fraud to non-fraud balance.

1.2 Increasing successful detections using data resampling

Undersampling

The most straightforward way to adjust the imbalance of your data, is to undersample the majority class, aka non-fraud cases, or oversample the minority class, aka the fraud cases. With undersampling, you take random draws from your non-fraud observations, to match the amount of fraud observations as seen on the picture.

Oversampling

You can implement resampling methods using Python’s imbalanced learn module. It is compatible with scikit-learn and allows you to implement these methods in just two lines of code. As you can see here, I import the package and take the Random Oversampler and assign it to method. I simply fit the method onto my original feature set X, and labels y, to obtained a resampled feature set X, and resampled y. I plot the datasets here side by side, such that you can see the effect of my resampling method. The darker blue color of the data points reflect that there are more identical data points now.

Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE)

The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique, or SMOTE, is another way of adjusting the imbalance by oversampling your minority observations, aka your fraud cases. But with SMOTE, we’re not just copying the minority class. Instead, as you see in this picture, SMOTE uses characteristics of nearest neighbors of fraud cases to create new synthetic fraud cases, and thereby avoids duplicating observations.

Which resampling method to use?

You might wonder which one of these methods is the best? Well, it depends very much on the situation. If you have very large amounts of data, and also many fraud cases, you might find it computationally easier to undersample, rather than to increase data even more. But in most cases, throwing away data is not desirable. When it comes to oversampling, SMOTE is more sophisticated as it does not duplicate data. But this only works well if your fraud cases are quite similar to each other. If fraud is spread out over your data and not very distinct, using nearest neighbors to create more fraud cases introduces a bit of noise in the data, as the nearest neighbors might not necessarily be fraud cases.

When to use resampling methods

One thing to keep in mind when using resampling methods, is to only resample on your training set. Your goal is to better train your model by giving it balanced amounts of data. Your goal is not to predict your synthetic samples. Always make sure your test data is free of duplicates or synthetic data, such that you can test your model on real data only. The way to do this, is to first split the data into a train and test set, as you can see here. I then resample the training set only. I fit my model into the resampled training data, and lastly, I obtain my performance metrics by looking at my original, not resampled, test data. These steps should look familiar to you.

1.2.1 Applying SMOTE

In the following example , we are going to re-balance our data using the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). Unlike ROS, SMOTE does not create exact copies of observations, but creates new, synthetic, samples that are quite similar to the existing observations in the minority class.

SMOTE is therefore slightly more sophisticated than just copying observations, so let’s apply SMOTE to our credit card data.

from imblearn.over_sampling import SMOTE

# Drop the Time column

df = df.drop('Time', axis=1)

# Run the prep_data function

X, y = prep_data(df)

# Define the resampling method

method = SMOTE()

# Create the resampled feature set

# apply SMOTE to the original X, y

X_resampled, y_resampled = method.fit_resample(X, y)

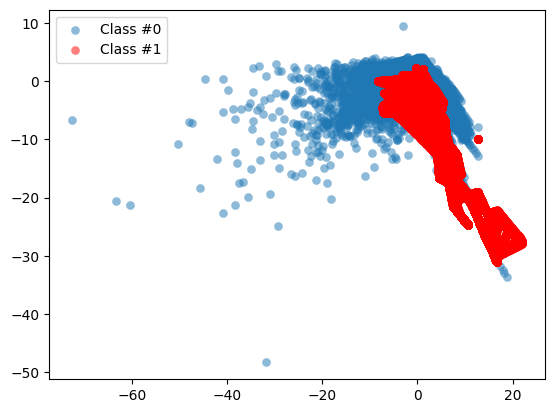

# Plot the resampled data

plot_data(X_resampled, y_resampled)

As you can see, our minority class is now much more prominently visible in our data. To see the results of SMOTE even better, we’ll compare it to the original data in the next section.

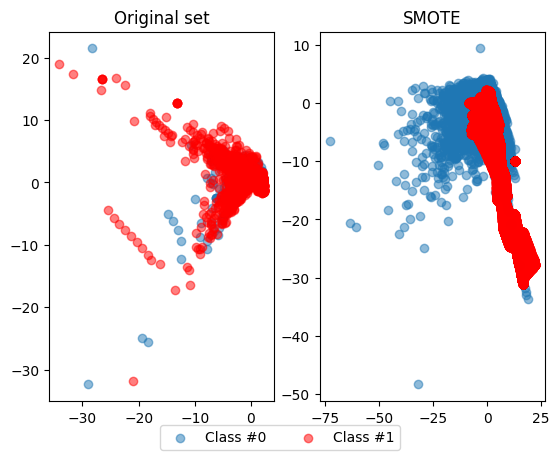

1.2.2 Compare SMOTE to original data

In the last exercise, you saw that using SMOTE suddenly gives us more observations of the minority class. Let’s compare those results to our original data, to get a good feeling for what has actually happened. Let’s have a look at the value counts again of our old and new data, and let’s plot the two scatter plots of the data side by side

def compare_plot(X_original,y_original,X_resampled,y_resampled, method):

# Start a plot figure

f, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2)

# sub-plot number 1, this is our normal data

c0 = ax1.scatter(X_original[y_original == 0, 0], X_original[y_original == 0, 1], label="Class #0",alpha=0.5)

c1 = ax1.scatter(X_original[y_original == 1, 0], X_original[y_original == 1, 1], label="Class #1",alpha=0.5, c='r')

ax1.set_title('Original set')

# sub-plot number 2, this is our oversampled data

ax2.scatter(X_resampled[y_resampled == 0, 0], X_resampled[y_resampled == 0, 1], label="Class #0", alpha=.5)

ax2.scatter(X_resampled[y_resampled == 1, 0], X_resampled[y_resampled == 1, 1], label="Class #1", alpha=.5,c='r')

ax2.set_title(method)

# some settings and ready to go

plt.figlegend((c0, c1), ('Class #0', 'Class #1'), loc='lower center',

ncol=2, labelspacing=0.)

#plt.tight_layout(pad=3)

return plt.show()# Print the value_counts on the original labels y

print(pd.value_counts(pd.Series(y)))

# Print the value_counts

print(pd.value_counts(pd.Series(y_resampled)))

# Run compare_plot

compare_plot(X_original, y_original, X_resampled, y_resampled, method='SMOTE')/tmp/ipykernel_3288/1066387134.py:2: FutureWarning: pandas.value_counts is deprecated and will be removed in a future version. Use pd.Series(obj).value_counts() instead.

print(pd.value_counts(pd.Series(y)))

/tmp/ipykernel_3288/1066387134.py:5: FutureWarning: pandas.value_counts is deprecated and will be removed in a future version. Use pd.Series(obj).value_counts() instead.

print(pd.value_counts(pd.Series(y_resampled)))0.0 284315

1.0 492

Name: count, dtype: int64

0.0 284315

1.0 284315

Name: count, dtype: int64

# Groupby categories and take the mean

print(df.groupby('category').mean())TypeError: agg function failed [how->mean,dtype->object]It should by now be clear that our SMOTE has balanced our data completely, and that the minority class is now equal in size to the majority class. Visualizing the data shows the effect on your data very clearly. In the next section, we’ll demonstrate that there are multiple ways to implement SMOTE and that each method will have a slightly different effect.

1.3 Fraud detection algorithms in action

As a data scientist, you’ll often be asked to defend your method of choice, so it is important to understand the intricacies of both methods.

Traditional fraud detection with rules based systems

Traditionally, fraud analysts use rules based systems for detection of fraud. For example in the case of credit cards, the analysts might create rules based on a location and block transactions from risky zip codes. They might also create rules to block transactions from cards used too frequently, for example in the last 30 minutes. Some of these rules can be highly efficient at catching fraud, whilst others are not and results in false alarm too often.

Drawbacks of using rules based systems

A major limitation of rules based systems, is that the thresholds per rule are fixed, and those do not adapt as fraudulent behavior changes over time. Also, it’s very difficult to determine what the right threshold should be. Second, with a rule, you’ll get a yes or no outcome, unlike with machine learning where you can get a probability value. With probabilities, you can much better fine tune the outcomes to the amount of cases you want to inspect as a fraud team. Effectively, with a machine learning model, you can easily determine how many false positives and false negatives are acceptable, and with rules that’s much harder. Rules based system also cannot capture the interaction of features like machine learning models can. So, for example, suppose the size of a transaction only matters in combination with the frequency, for determining fraudulent transactions. A rules based systems cannot really deal with that.

Why use machine learning for fraud detection?

Machine learning models don’t have these limitations. They will adapt to new data, and therefore can capture new fraudulent behavior. You are able to capture interactions between features, and can work with probabilities rather than yes/no answers. Machine learning models therefore typically have a better performance in fraud detection. However, machine learning models are not always the holy grail. Some simple rules might prove to be quite capable of catching fraud. You therefore want to explore whether you can combine models with rules, to improve overall performance.

1.3.1 Exploring the traditional way to catch fraud

In this example we are going to try finding fraud cases in our credit card dataset the “old way”. First we’ll define threshold values using common statistics, to split fraud and non-fraud. Then, use those thresholds on your features to detect fraud. This is common practice within fraud analytics teams. Statistical thresholds are often determined by looking at the mean values of observations.

# Get the mean for each group

df.groupby('Class').mean()

# Implement a rule for stating which cases are flagged as fraud

df['flag_as_fraud'] = np.where(np.logical_and(df.V1 < -3, df.V3 < -5), 1, 0)

# Create a crosstab of flagged fraud cases versus the actual fraud cases

print(pd.crosstab(df.Class, df.flag_as_fraud, rownames=['Actual Fraud'], colnames=['Flagged Fraud']))Flagged Fraud 0 1

Actual Fraud

0 283089 1226

1 322 170Not bad, with this rule, we detect 170 out of 492 fraud cases (34.5%), but can’t detect the other 322, and get 1,226 false positives (that is we flagged the transaction as fraud but it wasn’t). In the next section, we’ll see how this measures up to a machine learning model.

1.3.2 Using ML classification to catch fraud

In this exercise we’ll see what happens when we use a simple machine learning model on our credit card data instead. Let’s implement a Logistic Regression model.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report

from sklearn.metrics import confusion_matrix

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

# Create the training and testing sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=0)

# Fit a logistic regression model to our data

model = LogisticRegression()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Obtain model predictions

predicted = model.predict(X_test)

# Print the classifcation report and confusion matrix

print('Classification report:\n', classification_report(y_test, predicted))

conf_mat = confusion_matrix(y_true=y_test, y_pred=predicted)

print('Confusion matrix:\n', conf_mat)Classification report:

precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 1.00 1.00 85296

1.0 0.85 0.60 0.70 147

accuracy 1.00 85443

macro avg 0.93 0.80 0.85 85443

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 85443

Confusion matrix:

[[85281 15]

[ 59 88]]/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/linear_model/_logistic.py:458: ConvergenceWarning: lbfgs failed to converge (status=1):

STOP: TOTAL NO. of ITERATIONS REACHED LIMIT.

Increase the number of iterations (max_iter) or scale the data as shown in:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/preprocessing.html

Please also refer to the documentation for alternative solver options:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/linear_model.html#logistic-regression

n_iter_i = _check_optimize_result(We are getting far fewer false positives (15 compared with 1,226), so that’s an improvement. Also, we’re catching a higher percentage (59.9%) of fraud cases (88 out of 147) compared with 34.5% that is also better than before.

Do you understand why we have fewer observations to look at in the confusion matrix? Remember we are using only our test data to calculate the model results on. We’re comparing the crosstab on the full dataset from the last exercise, with a confusion matrix of only 30% of the total dataset, so that’s where that difference comes from.

In the next section, we’ll dive deeper into understanding these model performance metrics. Let’s now explore whether we can improve the prediction results even further with resampling methods.

1.3.3 Logistic regression combined with SMOTE

In this example, we’re going to take the Logistic Regression model from the previous exercise, and combine that with a SMOTE resampling method. We’ll show how to do that efficiently by using a pipeline that combines the resampling method with the model in one go. First, we need to define the pipeline that we’re going to use.

# This is the pipeline module we need for this from imblearn

from imblearn.pipeline import Pipeline

# Define which resampling method and which ML model to use in the pipeline

resampling = SMOTE()

model = LogisticRegression()

# Define the pipeline, tell it to combine SMOTE with the Logistic Regression model

pipeline = Pipeline([('SMOTE', resampling), ('Logistic Regression', model)])1.4 Using a pipeline

Now that we have our pipeline defined, aka combining a logistic regression with a SMOTE method, let’s run it on the data. We can treat the pipeline as if it were a single machine learning model.

# Split your data X and y, into a training and a test set and fit the pipeline onto the training data

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=0)

# Fit your pipeline onto your training set and obtain predictions by fitting the model onto the test data

pipeline.fit(X_train, y_train)

predicted = pipeline.predict(X_test)

# Obtain the results from the classification report and confusion matrix

print('Classifcation report:\n', classification_report(y_test, predicted))

conf_mat = confusion_matrix(y_true=y_test, y_pred=predicted)

print('Confusion matrix:\n', conf_mat)Classifcation report:

precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 0.98 0.99 85296

1.0 0.09 0.90 0.16 147

accuracy 0.98 85443

macro avg 0.55 0.94 0.58 85443

weighted avg 1.00 0.98 0.99 85443

Confusion matrix:

[[83970 1326]

[ 15 132]]/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/linear_model/_logistic.py:458: ConvergenceWarning: lbfgs failed to converge (status=1):

STOP: TOTAL NO. of ITERATIONS REACHED LIMIT.

Increase the number of iterations (max_iter) or scale the data as shown in:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/preprocessing.html

Please also refer to the documentation for alternative solver options:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/linear_model.html#logistic-regression

n_iter_i = _check_optimize_result(As we can see, the SMOTE slightly improves our results. We now manage to find 132 out of 147 cases of fraud (89.8%), but we have a slightly higher number of false positives, 1,326 cases.

Remember, resampling does not necessarily lead to better results. When the fraud cases are very spread and scattered over the data, using SMOTE can introduce a bit of bias. Nearest neighbors aren’t necessarily also fraud cases, so the synthetic samples might ‘confuse’ the model slightly.

In the next sections, we’ll learn how to also adjust our machine learning models to better detect the minority fraud cases.

2 Fraud detection using labeled data

In this section we will learn how to flag fraudulent transactions with supervised learning. You will use classifiers, adjust them, and compare them to find the most efficient fraud detection model.

2.1 Review of classification methods

What is classification?

Classification is the problem of identifying to which class a new observation belongs, on the basis of a training set of data containing observations whose class is known. Classes are sometimes called targets, labels or categories. For example, spam detection in email service providers can be identified as a classification problem. This is a binary classification since there are only two classes as spam and not spam. Fraud detection is a classification problem, as we try to predict whether observations are fraudulent, yes or no. Lastly, assigning a diagnosis to a patient based on characteristics of a tumor, malignant or benign, is a classification problem. Classification problems normally have a categorical output like a yes or no, 1 or 0, True or False. In the case of fraud detection, the negative non-fraud class is the majority class, whereas the fraud cases are the minority class.

Classification methods commonly used for fraud detection

Neural networks

They are capable of fitting highly non-linear models to our data. They tend to be slightly more complex to implement than most of the other classifiers.

Decision trees

As you can see in the picture, decision trees give very transparent results, that are easily interpreted by fraud analysts. Nonetheless, they are prone to overfit to your data.

Random Forest

Random forests are a more robust option to use, as they construct a multitude of decision trees when training your model and outputting the class that is the mode or mean predicted class of all the individual trees. To be more precise, a random forest consists of a collection of trees on a random subset of features. Final predictions are the combined results of those trees. Random forests can handle complex data and are not prone to overfit. They are interpretable by looking at feature importance, and can be adjusted to work well on highly imbalanced data. The only drawback is that they can be computationally quite heavy to run. Nonetheless, random forests are very popular for fraud detection.

2.1.1 Natural hit rate

First let’s explore how prevalent fraud is in the dataset, to understand what the “natural accuracy” is, if we were to predict everything as non-fraud. It is important to understand which level of “accuracy” you need to “beat” in order to get a better prediction than by doing nothing. In the following exercises, we’ll create a random forest classifier for fraud detection. That will serve as the “baseline” model that we’re going to try to improve.

# Count the total number of observations from the length of y

total_obs = len(y)

# Count the total number of non-fraudulent observations

non_fraud = [obs for obs in y if obs == 0]

count_non_fraud = non_fraud.count(0)

# Calculate the percentage of non fraud observations in the dataset

percentage = (float(count_non_fraud)/float(total_obs)) * 100

# Print the percentage: this is our "natural accuracy" by doing nothing

print(percentage)99.82725143693798This tells us that by doing nothing, we would be correct in 99.8% of the cases. So now you understand, that if we get an accuracy of less than this number, our model does not actually add any value in predicting how many cases are correct. Let’s see how a random forest does in predicting fraud in our data.

2.1.2 Random Forest Classifier

Let’s now create a random forest classifier for fraud detection. Hopefully we can do better than the baseline accuracy we just calculated, which was roughly 99.8% This model will serve as the “baseline” model that you’re going to try to improve.

# Import the random forest model from sklearn

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

# Split your data into training and test set

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state=0)

# Define the model as the random forest

model = RandomForestClassifier(random_state=5)Let’s see how our Random Forest model performs without doing anything special to it :

# Fit the model to our training set

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Obtain predictions from the test data

predicted = model.predict(X_test)# Print the accuracy performance metric

print(accuracy_score(y_test, predicted))0.9995201479348805The Random Forest model achieves an accuracy score of 99.95%.

2.2 Performance Evaluation

Accuracy isn’t everything

As you can see on these two images, accuracy is not a reliable performance metric when working with highly imbalanced data, as is the case in fraud detection. By doing nothing, aka predicting everything is the majority class, in the picture on the right, you often obtain a higher accuracy than by actually trying to build a predictive model, in the picture on the left. So let’s discuss other performance metrics that are actually informative and reliable.

False positives, false negatives, and actual fraud

First of all, we need to understand the concepts of false positives, false negatives etc really well for fraud detection. Let’s refresh that for a moment.

The true positives and true negatives are the cases you are predicting correct, in our case, fraud and non-fraud. The images on the top left and bottom right are true negatives and true positives, respectively. The false negatives as seen in the bottom left, is predicting the person is not pregnant, but actually is. So these are the cases of fraud you are not catching with your model. The false positives in the top right are the cases that we predict to be pregnant, but aren’t actually. These are “false alarm” cases, and can result in a burden of work whilst there actually is nothing going on.

Depending on the business case, one might care more about false negatives than false positives, or vice versa. A credit card company might want to catch as much fraud as possible and reduce false negatives, as fraudulent transactions can be incredibly costly, whereas a false alarm just means someone’s transaction is blocked.

On the other hand, an insurance company can not handle many false alarms, as it means getting a team of investigators involved for each positive prediction.

Precision-recall tradeoff

The credit card company, therefore, wants to optimize for recall, whereas the insurance company cares more for precision.

Precision is the fraction of actual fraud cases out of all predicted fraud cases, ie, the true positives relative to the true positives plus false positives

Recall is the fraction of predicted fraud cases out of all the actual fraud cases, ie, the true positives relative to the true positives plus false negatives. Typically, precision and recall are inversely related.

Basically as precision increases, recall falls and vice versa. You can plot the tradeoff between the two in the precision-recall curve, as seen here on the left.

The F-score weighs both precision and recall into one measure, so if you want to use a performance metric that takes into account a balance between precision and recall, F-score is the one to use.

Obtaining performance metrics

Obtaining precision and recall from scikit-learn is relatively straightforward.

from sklearn.metrics import precision_recall_curve

from sklearn.metrics import average_precision_score

average precision = average_precision_score(y_test, predicted)The average precision is calculated with the average_precision_score, which you need to run on the actual labels y_test and your predictions. The curve is obtained in a similar way, which you can then plot to look at the trade-off between the two.

Precision-recall Curve

precision, recall, _ = precision_recall_curve(y_test, predicted)This returns the following graph.

ROC curve to compare algorithms

Another useful tool in the performance toolbox is the ROC curve. ROC stands for receiver operating characteristic curve, and is created by plotting the true positive rate against the false positive rate at various threshold settings. The ROC curve is very useful for comparing performance of different algorithms for your fraud detection problem. The “area under the ROC curve”-metric is easily obtained by getting the model probabilities like this:

probs = model.predict_proba(X_test)and then comparing those with the actual labels.

print(metrics.roc_auc_score(y_test, probs[:,1]))Confusion matrix and classification report

The confusion matrix and classification report are an absolute must have for fraud detection performance. You can obtain these from the scikit-learn metrics package.

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report, confusion_matrix

predicted = model.predict(X_test)

print(classification_report(y_test,predicted))You need the model predictions for these, so not the probabilities. The classification report gives you precision, recall, and F1-score across the different labels. The confusion matrix plots the false negatives, false positives, etc for you.

print(confusion_matrix(y_test, predicted))2.2.1 Performance metrics for the RF model

# Import the packages to get the different performance metrics

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report, confusion_matrix, roc_auc_score

# Obtain the predictions from our random forest model

predicted = model.predict(X_test)

# Predict probabilities

probs = model.predict_proba(X_test)

# Print the ROC curve, classification report and confusion matrix

print(roc_auc_score(y_test, probs[:,1]))

print(classification_report(y_test, predicted))

print(confusion_matrix(y_test, predicted))0.9406216622833715

precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 1.00 1.00 85296

1.0 0.94 0.77 0.85 147

accuracy 1.00 85443

macro avg 0.97 0.88 0.92 85443

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 85443

[[85289 7]

[ 34 113]]We have now obtained more meaningful performance metrics that tell us how well the model performs, given the highly imbalanced data that we’re working with. The model predicts 120 cases of fraud, out of which 113 are actual fraud. We have only 7 false positives. This is really good, and as a result we have a very high precision score. We however don’t catch 34 cases of actual fraud. Recall is therefore not as good as precision. Let’s try to improve that.

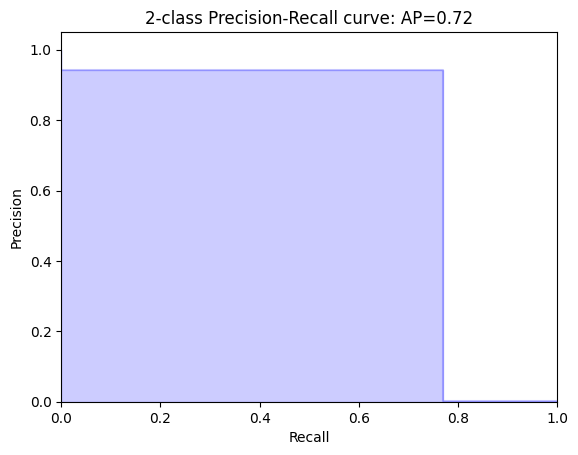

2.2.2 Plotting the Precision Recall Curve

We can also plot a Precision-Recall curve, to investigate the trade-off between the two in our model. In this curve Precision and Recall are inversely related; as Precision increases, Recall falls and vice-versa. A balance between these two needs to be achieved in our model, otherwise we might end up with many false positives, or not enough actual fraud cases caught. To achieve this and to compare performance, the precision-recall curves come in handy.

from sklearn.metrics import average_precision_score

# Calculate average precision and the PR curve

average_precision = average_precision_score(y_test, predicted)def plot_pr_curve(recall, precision, average_precision):

plt.step(recall, precision, color='b', alpha=0.2, where='post')

plt.fill_between(recall, precision, step='post', alpha=0.2, color='b')

plt.xlabel('Recall')

plt.ylabel('Precision')

plt.ylim([0.0, 1.05])

plt.xlim([0.0, 1.0])

plt.title('2-class Precision-Recall curve: AP={0:0.2f}'.format(average_precision))

plt.show()from sklearn.metrics import precision_recall_curve

# Obtain precision and recall

precision, recall, _ = precision_recall_curve(y_test, predicted)

# Plot the recall precision tradeoff

plot_pr_curve(recall, precision, average_precision)

2.3 Adjusting your algorithm weights

Balanced weights

When training a model for fraud detection, you want to try different options and setting to get the best recall-precision tradeoff possible. In scikit-learn there are two simple options to tweak your model for heavily imbalanced fraud data.

There is the balanced mode, and balanced_subsample mode, that you can assign to the weight argument when defining the model.

model = RandomForestClassifier(class_weight='balanced')

model = RandomForestClassifier(class_weight='balanced_subsample')The balanced mode uses the values of y to automatically adjust weights inversely proportional to class frequencies in the input data. The balanced_subsample mode is the same as the balanced option, except that weights are calculated again at each iteration of growing a tree in the random forest. This latter option is therefore only applicable for the random forest model. The balanced option is however also available for many other classifiers, for example the logistic regression has the option, as well as the SVM model.

Hyperparameter tuning for fraud detection

The weight option also takes a manual input. This allows you to adjust weights not based on the value counts relative to sample, but to whatever ratio you like. So if you just want to upsample your minority class slightly, then this is a good option. All the classifiers that have the weight option available should have this manual setting also. Moreover, the random forest takes many other options you can use to optimize the model; you call this hyperparameter tuning.

model = RandomForestClassifier(class_weight={0:1, 1:4}, random_state=1)

model = LogisticRegression(class_weight={0:1, 1:4}, random_state=1)You can, for example, change the shape and size of the trees in the random forest by adjusting leaf size and tree depth. One of the most important settings are the number of trees in the forest, called number of estimators, and the number of features considered for splitting at each leaf node, indicated by max_features. Moreover, you can change the way the data is split at each node, as the default is to split on the gini coefficient.

model = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=10, criterion = 'gini', max_depth=None, min_samples_split=2, min_samples_leaf=1, max_features='auto', n_jobs=1, class_weight=None)Using GridSearchCV

A smarter way of hyperparameter tuning your model is to use GridSearchCV. GridSearchCV evaluates all combinations of parameters we define in the parameter grid. This is an example of a parameter grid specifically for a random forest model. Let’s define the machine learning model we’ll use. And now, let’s put it into a grid search. You pass in the model, the parameter grid, and we’ll tell it how often to cross-validate. Most importantly, you need to define a scoring metric to evaluate the models on. This is incredibly important in fraud detection. The default option here would be accuracy, so if you don’t define this, your models are ranked based on accuracy, which you already know is useless. You therefore need to pass the option precision, recall, or F1 here. Let’s go with F1 for this example:

Finding the best model with GridSearchCV

Once you have fitted your GridSearchCV and model to the data, you can obtain the parameters belonging to the optimal model by using the best parameters function.

grid_search_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

grid_search_model.best_params_Mind you, GridSearchCV is computationally very heavy to run. Depending on the size of your data, and number of parameters in the grid, this can take up to many hours to complete, so make sure to save the results. You can easily get the results for the best_estimator that gives the best_score; these results are all stored. The best score is the mean cross-validated score of the best_estimator, which of course also depends on the scoring option you gave earlier. As you chose F1 before, you’ll get the best F1 sore here.

grid_search.best_estimator_

grid_search.best_score_2.3.1 Model adjustments

# Define the model with balanced subsample

model = RandomForestClassifier(class_weight='balanced_subsample', random_state=5)

# Fit your training model to your training set

model.fit(X_train, y_train)# Obtain the predicted values and probabilities from the model

predicted = model.predict(X_test)

probs = model.predict_proba(X_test)

# Print the roc_auc_score, the classification report and confusion matrix

print(roc_auc_score(y_test, probs[:,1]))

print(classification_report(y_test, predicted))

print(confusion_matrix(y_test, predicted))0.9407294501931329

precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 1.00 1.00 85296

1.0 0.95 0.76 0.84 147

accuracy 1.00 85443

macro avg 0.97 0.88 0.92 85443

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 85443

[[85290 6]

[ 36 111]]We can see that the model results don’t improve drastically. We now have 6 false positives (compared to 7), and now 36 instead of 34 false negatives, i.e. cases of fraud we are not catching.

2.3.2 Adjusting our Random Forest to fraud detection

In this example we will explore the options for the random forest classifier, by assigning weights and tweaking the shape of the decision trees in the forest. We’ll define weights manually, to be able to off-set that imbalance slightly.

df.Class.value_counts()Class

0 284315

1 492

Name: count, dtype: int64In our case we have 492 fraud to 284,315 non-fraud cases, so by setting the weight ratio to 1:290, we get to 142,680 : 284315 (1/3 fraud to 2/3 non-fraud) ratio, which is good enough for training the model on.

def get_model_results(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, model):

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

predicted = model.predict(X_test)

probs = model.predict_proba(X_test)

print (classification_report(y_test, predicted))

print (confusion_matrix(y_test, predicted))# Change the model options

model = RandomForestClassifier(bootstrap=True, class_weight={0:1, 1:290}, criterion='entropy',

# Change depth of model

max_depth=10,

# Change the number of samples in leaf nodes

min_samples_leaf=10,

# Change the number of trees to use

n_estimators=20, n_jobs=-1, random_state=5)

# Run the function get_model_results

get_model_results(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, model) precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 1.00 1.00 85296

1.0 0.85 0.80 0.83 147

accuracy 1.00 85443

macro avg 0.92 0.90 0.91 85443

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 85443

[[85275 21]

[ 29 118]]WE can see by smartly defining more options in the model, we can obtain better predictions. We have effectively reduced the number of false negatives (from 36 to 29), i.e. we are catching more cases of fraud, whilst keeping the number of false positives relatively low (21). In this example we manually changed the options of the model. There is a smarter way of doing it, by using GridSearchCV, which you’ll see in the next section.

2.3.3 GridSearchCV to find optimal parameters

In this example we will tweak our model in a less “random” way, by leveraging GridSearchCV.

With GridSearchCV you can define which performance metric to score the options on. Since for fraud detection we are mostly interested in catching as many fraud cases as possible, we can optimize your model settings to get the best possibleRecall score. If we also cared about reducing the number of false positives, we could optimize on F1-score, which provides a Precision-Recall trade-off.

from sklearn.model_selection import GridSearchCV# Define the parameter sets to test

# n_estimators = number of trees

# criterion refer to way trees split

param_grid = {'n_estimators': [1, 30], 'max_features': ['auto', 'log2'], 'max_depth': [4, 8], 'criterion': ['gini', 'entropy']

}

# Define the model to use

model = RandomForestClassifier(random_state=5)

# Combine the parameter sets with the defined model

CV_model = GridSearchCV(estimator=model, param_grid=param_grid, cv=5, scoring='recall', n_jobs=-1)

# Fit the model to our training data and obtain best parameters

CV_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

CV_model.best_params_/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn(

/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/ensemble/_forest.py:424: FutureWarning: `max_features='auto'` has been deprecated in 1.1 and will be removed in 1.3. To keep the past behaviour, explicitly set `max_features='sqrt'` or remove this parameter as it is also the default value for RandomForestClassifiers and ExtraTreesClassifiers.

warn({'criterion': 'entropy',

'max_depth': 8,

'max_features': 'log2',

'n_estimators': 30}2.3.4 Model results using GridSearchCV

# Input the optimal parameters in the model

model = RandomForestClassifier(class_weight={0:1,1:290}, criterion='entropy',

n_estimators=30, max_features='log2', min_samples_leaf=10, max_depth=8, n_jobs=-1, random_state=5)

# Get results from your model

get_model_results(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, model) precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 1.00 1.00 85296

1.0 0.83 0.82 0.82 147

accuracy 1.00 85443

macro avg 0.92 0.91 0.91 85443

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 85443

[[85272 24]

[ 27 120]]We managed to improve our model even further. The number of false negatives has now been slightly reduced even further (from 29 to 27), which means we are catching more cases of fraud. However, we can see that the number of false positives actually went up (from 21 to 24).

That is that Precision-Recall trade-off in action.

To decide which final model is best, we need to take into account how bad it is not to catch fraudsters, versus how many false positives the fraud analytics team can deal with. Ultimately, this final decision should be made by you and the fraud team together.

2.4 Ensemble methods

What are ensemble methods: bagging versus stacking

Ensemble methods are techniques that create multiple machine learning models and then combine them to produce a final result. Ensemble methods usually produce more accurate predictions than a single model would. In fact, you’ve already worked with an ensemble method during the exercises. The random forest classifier is an ensemble of decision trees, and is described as a bootstrap aggregation, or bagging ensemble method. In a random forest, you train models on random subsamples of your data and aggregate the results by taking the average prediction of all of the trees.

Stacking ensemble methods

In this picture, you see a stacking ensemble method. In this case, multiple models are combined via a voting rule on the model outcome. The base level models are each trained based on the complete training set. So, unlike with the bagging method, you do not train your models on a subsample. In the stacking ensemble method, you can combine algorithms of different types. We’ll practice this in the exercises.

Why use ensemble methods for fraud detection

The goal of any machine learning problem is to find a single model that will best predict the wanted outcome. Rather than making one model, and hoping this model is the best or most accurate predictor, you can make use of ensemble methods. Ensemble methods take a myriad of models into account, and average those models to produce one final model. This ensures that your predictions are robust and less likely to be the result of overfitting. Moreover, ensemble methods can improve overall performance of fraud detection, especially combining models with different recall and precision scores. They have therefore been a winning formula at many Kaggle competitions recently.

Voting classifier

he voting classifier available in scikit-learn is an easy way to implement an ensemble model. You start by importing the voting classifier, available from the ensemble methods package. Let’s define three models to use in our ensemble model, in this case let’s use a random forest, a logistic regression, and a Naive Bayes model. The next step is to combine these three into the ensemble model like this, and assign a rule to combine the model results. In this case, let’s use a hard voting rule. That option uses the predicted class labels and takes the majority vote. The other option is soft voting. This rule takes the average probability by combining the predicted probabilities of the individual models. You can then simply use the ensemble_model as you would any other machine learning model, ie you can fit and use the model to predict classes. Last thing to mention is that you can also assign weights to the model predictions in the ensemble, which can be useful, for example, when you know one model outperforms the others significantly.

Reliable labels for fraud detection

In this section we have seen how to detect fraud when there are labels to train a model on. However, in real life, it is unlikely that you will have truly unbiased reliable labels for you model. For example, in credit card fraud you often will have reliable labels, in which case you want to use these methods you’ve just learned. However, in most other cases, you will need to rely on unsupervised learning techniques to detect fraud. You will learn how to do this in a later section.

2.4.1 Logistic Regression

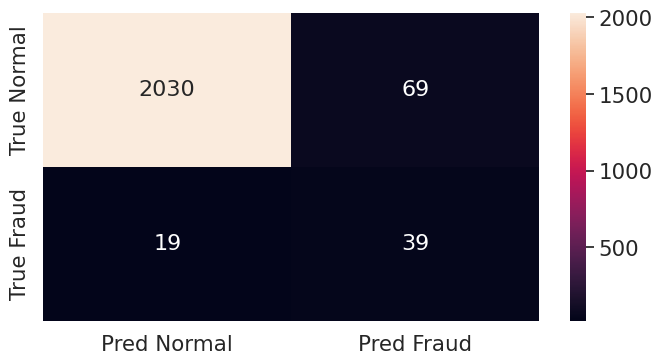

We wil now combine three algorithms into one model with the VotingClassifier. This allows us to benefit from the different aspects from all models, and hopefully improve overall performance and detect more fraud. The first model, the Logistic Regression, has a slightly higher recall score than our optimal Random Forest model, but gives a lot more false positives. We’ll also add a Decision Tree with balanced weights to it.

df = pd.read_csv('data/creditcard.csv')

df| Time | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | V9 | ... | V21 | V22 | V23 | V24 | V25 | V26 | V27 | V28 | Amount | Class | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.0 | -1.359807 | -0.072781 | 2.536347 | 1.378155 | -0.338321 | 0.462388 | 0.239599 | 0.098698 | 0.363787 | ... | -0.018307 | 0.277838 | -0.110474 | 0.066928 | 0.128539 | -0.189115 | 0.133558 | -0.021053 | 149.62 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.0 | 1.191857 | 0.266151 | 0.166480 | 0.448154 | 0.060018 | -0.082361 | -0.078803 | 0.085102 | -0.255425 | ... | -0.225775 | -0.638672 | 0.101288 | -0.339846 | 0.167170 | 0.125895 | -0.008983 | 0.014724 | 2.69 | 0 |

| 2 | 1.0 | -1.358354 | -1.340163 | 1.773209 | 0.379780 | -0.503198 | 1.800499 | 0.791461 | 0.247676 | -1.514654 | ... | 0.247998 | 0.771679 | 0.909412 | -0.689281 | -0.327642 | -0.139097 | -0.055353 | -0.059752 | 378.66 | 0 |

| 3 | 1.0 | -0.966272 | -0.185226 | 1.792993 | -0.863291 | -0.010309 | 1.247203 | 0.237609 | 0.377436 | -1.387024 | ... | -0.108300 | 0.005274 | -0.190321 | -1.175575 | 0.647376 | -0.221929 | 0.062723 | 0.061458 | 123.50 | 0 |

| 4 | 2.0 | -1.158233 | 0.877737 | 1.548718 | 0.403034 | -0.407193 | 0.095921 | 0.592941 | -0.270533 | 0.817739 | ... | -0.009431 | 0.798278 | -0.137458 | 0.141267 | -0.206010 | 0.502292 | 0.219422 | 0.215153 | 69.99 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 284802 | 172786.0 | -11.881118 | 10.071785 | -9.834783 | -2.066656 | -5.364473 | -2.606837 | -4.918215 | 7.305334 | 1.914428 | ... | 0.213454 | 0.111864 | 1.014480 | -0.509348 | 1.436807 | 0.250034 | 0.943651 | 0.823731 | 0.77 | 0 |

| 284803 | 172787.0 | -0.732789 | -0.055080 | 2.035030 | -0.738589 | 0.868229 | 1.058415 | 0.024330 | 0.294869 | 0.584800 | ... | 0.214205 | 0.924384 | 0.012463 | -1.016226 | -0.606624 | -0.395255 | 0.068472 | -0.053527 | 24.79 | 0 |

| 284804 | 172788.0 | 1.919565 | -0.301254 | -3.249640 | -0.557828 | 2.630515 | 3.031260 | -0.296827 | 0.708417 | 0.432454 | ... | 0.232045 | 0.578229 | -0.037501 | 0.640134 | 0.265745 | -0.087371 | 0.004455 | -0.026561 | 67.88 | 0 |

| 284805 | 172788.0 | -0.240440 | 0.530483 | 0.702510 | 0.689799 | -0.377961 | 0.623708 | -0.686180 | 0.679145 | 0.392087 | ... | 0.265245 | 0.800049 | -0.163298 | 0.123205 | -0.569159 | 0.546668 | 0.108821 | 0.104533 | 10.00 | 0 |

| 284806 | 172792.0 | -0.533413 | -0.189733 | 0.703337 | -0.506271 | -0.012546 | -0.649617 | 1.577006 | -0.414650 | 0.486180 | ... | 0.261057 | 0.643078 | 0.376777 | 0.008797 | -0.473649 | -0.818267 | -0.002415 | 0.013649 | 217.00 | 0 |

284807 rows × 31 columns

# Drop the Time column

df = df.drop('Time', axis=1)def prep_data(df):

X = df.iloc[:, 1:29]

X = np.array(X).astype(np.float64)

y = df.iloc[:, 29]

y=np.array(y).astype(np.float64)

return X,y# Create X and y from the prep_data function

X_original, y_original = prep_data(df)# Create the training and testing sets

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X_original, y_original, test_size=0.3, random_state=0)X_train.shape(199364, 28)y_trainarray([0., 0., 0., ..., 0., 0., 0.])def get_model_results(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, model):

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

predicted = model.predict(X_test)

probs = model.predict_proba(X_test)

print (classification_report(y_test, predicted))

print (confusion_matrix(y_test, predicted))

# Define the Logistic Regression model with weights

model = LogisticRegression(class_weight={0:1, 1:290}, random_state=5)

# Get the model results

get_model_results(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, model) precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 0.99 0.99 85296

1.0 0.11 0.89 0.20 147

accuracy 0.99 85443

macro avg 0.56 0.94 0.60 85443

weighted avg 1.00 0.99 0.99 85443

[[84255 1041]

[ 16 131]]/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/linear_model/_logistic.py:458: ConvergenceWarning: lbfgs failed to converge (status=1):

STOP: TOTAL NO. of ITERATIONS REACHED LIMIT.

Increase the number of iterations (max_iter) or scale the data as shown in:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/preprocessing.html

Please also refer to the documentation for alternative solver options:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/linear_model.html#logistic-regression

n_iter_i = _check_optimize_result(As you can see the Logistic Regression has quite different performance from the Random Forest. More false positives: 1,041 compared with 24, but also a better Recall, 0.89 compared to 0.82. It will therefore be a useful addition to the Random Forest in an ensemble model. Let’s give that a try.

2.4.2 Voting Classifier

Let’s now combine three machine learning models into one, to improve our Random Forest fraud detection model from before. We’ll combine our usual Random Forest model, with the Logistic Regression from the previous exercise, with a simple Decision Tree.

# Define the three classifiers to use in the ensemble

clf1 = LogisticRegression(class_weight={0:1, 1:15}, random_state=5)

clf2 = RandomForestClassifier(class_weight={0:1, 1:290}, criterion='gini', max_depth=8, max_features='log2',

min_samples_leaf=10, n_estimators=30, n_jobs=-1, random_state=5)

clf3 = DecisionTreeClassifier(random_state=5, class_weight="balanced")

# Combine the classifiers in the ensemble model

ensemble_model = VotingClassifier(estimators=[('lr', clf1), ('rf', clf2), ('dt', clf3)], voting='soft') # predict_proba is not available when voting='hard'

# Get the results

get_model_results(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, ensemble_model)/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/linear_model/_logistic.py:458: ConvergenceWarning: lbfgs failed to converge (status=1):

STOP: TOTAL NO. of ITERATIONS REACHED LIMIT.

Increase the number of iterations (max_iter) or scale the data as shown in:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/preprocessing.html

Please also refer to the documentation for alternative solver options:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/linear_model.html#logistic-regression

n_iter_i = _check_optimize_result( precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 1.00 1.00 85296

1.0 0.84 0.80 0.82 147

accuracy 1.00 85443

macro avg 0.92 0.90 0.91 85443

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 85443

[[85273 23]

[ 30 117]]We see that by combining the classifiers, we can take the best of multiple models. We’ve slightly decreased the cases of fraud we are catching from 120 to 117, and also reduced the number of false positives from 24 to 23. If you do care about catching as many fraud cases as you can, whilst keeping the false positives low, this is a pretty good trade-off. The Logistic Regression as a standalone was quite bad in terms of false positives, and the Random Forest was worse in terms of false negatives. By combining these together we managed to improve performance.

2.4.3 Adjust weights within the Voting Classifier

You’ve just seen that the Voting Classifier allows you to improve your fraud detection performance, by combining good aspects from multiple models. Now let’s try to adjust the weights we give to these models. By increasing or decreasing weights you can play with how much emphasis you give to a particular model relative to the rest. This comes in handy when a certain model has overall better performance than the rest, but you still want to combine aspects of the others to further improve your results.

# Define the ensemble model, weighting 2nd classifier 4 to 1 with the rest

ensemble_model = VotingClassifier(estimators=[('lr', clf1), ('rf', clf2), ('gnb', clf3)], voting='soft', weights=[1, 4, 1], flatten_transform=True)

# Get results

get_model_results(X_train, y_train, X_test, y_test, ensemble_model)/home/stephen137/mambaforge/lib/python3.10/site-packages/sklearn/linear_model/_logistic.py:458: ConvergenceWarning: lbfgs failed to converge (status=1):

STOP: TOTAL NO. of ITERATIONS REACHED LIMIT.

Increase the number of iterations (max_iter) or scale the data as shown in:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/preprocessing.html

Please also refer to the documentation for alternative solver options:

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/linear_model.html#logistic-regression

n_iter_i = _check_optimize_result( precision recall f1-score support

0.0 1.00 1.00 1.00 85296

1.0 0.83 0.82 0.82 147

accuracy 1.00 85443

macro avg 0.92 0.91 0.91 85443

weighted avg 1.00 1.00 1.00 85443

[[85272 24]

[ 27 120]]We have detected another 3 fraud cases and only conceded one additional false positive.

The weight option allows you to play with the individual models to get the best final mix for your fraud detection model. Now that we have finalized fraud detection with supervised learning, let’s have a look at how fraud detection can be done when you don’t have any labels to train on.

3. Fraud detection using unlabeled data

This section focuses on using unsupervised learning techniques to detect fraud. We will segment customers, use K-means clustering and other clustering algorithms to find suspicious occurrences in our data.

3.1 Normal versus abnormal behaviour

Fraud detection without labels

When you can’t rely on fraud labels, you can use unsupervised learning to detect suspicious behavior. Suspicious behavior is behavior that is very uncommon in your data, for example, very large transactions, or many transactions in a short period of time. Such behavior often is an indication of fraud, but of course can also just be uncommon but not fraudulent. This type of fraud detection is challenging, because you don’t have trustworthy labels to check your model results against. But, in fact, not having labels is the reality for many cases of fraud detection.

What is normal behavior?

In order to detect suspicious behavior, you need to understand your data very well. A good exploratory data analysis, including distribution plots, checking for outliers and correlations etc, is crucial. The fraud analysts can help you understand what are normal values for your data, and also what typifies fraudulent behavior. Moreover, you need to investigate whether your data is homogeneous, or whether different types of clients display very different behavior. What is normal for one does not mean it’s normal for another. For example, older age groups might have much higher total amount of health insurance claims than younger people. Or, a millionaire might make much larger transactions on average than a student. If that is the case in your data, you need to find homogeneous subgroups of data that are similar, such that you can look for abnormal behavior within subgroups.

Customer segmentation: normal behavior within segments

So what can you think about when checking for segments in your data? First of all, you need to make sure all your data points are the same type. By type I mean: are they individuals, groups of people, companies, or governmental organizations? Then, think about whether the data points differ on, for example spending patterns, age, location, or frequency of transactions. Especially for credit card fraud, location can be a big indication for fraud. But this also goes for e-commerce sites; where is the IP address located, and where is the product ordered to ship? If they are far apart that might not be normal for most clients, unless they indicate otherwise. Last thing to keep in mind, is that you have to create a separate model on each segment, because you want to detect suspicious behavior within each segment. But that means that you have to think about how to aggregate the many model results back into one final list.

3.1.1 Exploring your data

df = pd.read_csv('data/banksim.csv')

df| Unnamed: 0 | age | gender | category | amount | fraud | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 171915 | 3 | F | es_transportation | 49.7100 | 0 |

| 1 | 426989 | 4 | F | es_health | 39.2900 | 0 |

| 2 | 310539 | 3 | F | es_transportation | 18.7600 | 0 |

| 3 | 215216 | 4 | M | es_transportation | 13.9500 | 0 |

| 4 | 569244 | 2 | M | es_transportation | 49.8700 | 0 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 7195 | 260136 | 5 | M | es_hotelservices | 236.1474 | 1 |

| 7196 | 56643 | 5 | F | es_hotelservices | 139.6000 | 1 |

| 7197 | 495817 | 1 | F | es_travel | 236.1474 | 1 |

| 7198 | 333170 | 1 | M | es_hotelservices | 236.1474 | 1 |

| 7199 | 579286 | 4 | F | es_health | 236.1474 | 1 |

7200 rows × 6 columns

df.drop('Unnamed: 0', axis=1, inplace=True)# Get the dataframe shape

df.shape(7200, 5)# Display the first 5 rows

df.head()| age | gender | category | amount | fraud | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | F | es_transportation | 49.71 | 0 |

| 1 | 4 | F | es_health | 39.29 | 0 |

| 2 | 3 | F | es_transportation | 18.76 | 0 |

| 3 | 4 | M | es_transportation | 13.95 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 | M | es_transportation | 49.87 | 0 |

# Group by 'category' and calculate the mean of 'value'

df.groupby('category')['fraud'].mean()category

es_barsandrestaurants 0.022472

es_contents 0.000000

es_fashion 0.020619

es_food 0.000000

es_health 0.242798

es_home 0.208333

es_hotelservices 0.548387

es_hyper 0.125000

es_leisure 1.000000

es_otherservices 0.600000

es_sportsandtoys 0.657895

es_tech 0.179487

es_transportation 0.000000

es_travel 0.944444

es_wellnessandbeauty 0.060606

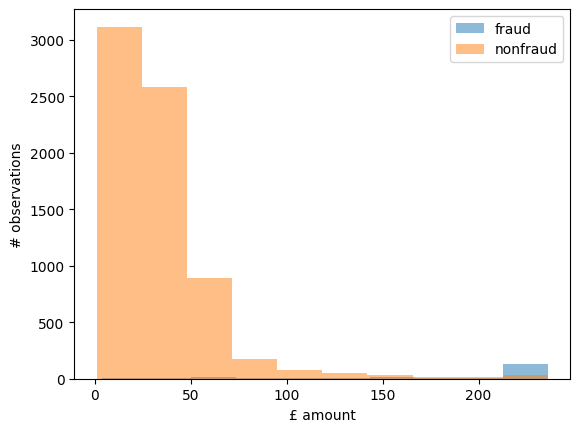

Name: fraud, dtype: float64You can see from the category averages that fraud is more prevalent in the leisure, travel and sports categories.

3.1.2 Customer segmentation